By Miguel A. Melendez, Staff Writer

Karl Holmes Jr. met his father for the first time when he was 5 years old. He was 11 by the time he saw him again.

In December, the Muir senior will drive to San Quentin State Prison to visit Holmes Sr., 35, who’s spent the last 15 years on Death Row along with Lorenzo Newborn and Herbert McClain for their conviction in the killings of three Pasadena children on Halloween night in 1993.

Holmes’ mother, Wanda Martin, wasn’t a constant presence until just two years ago, when Holmes moved in with her, he said. She was in and out of his life, and Holmes during that time was under the care of his uncle, former Muir star running back Darick Holmes.

With seemingly every excuse in the book to turn his back on life, Holmes decided he wouldn’t be just another statistic. In spite of his parent’s troubled history, success became Holmes’ only option.

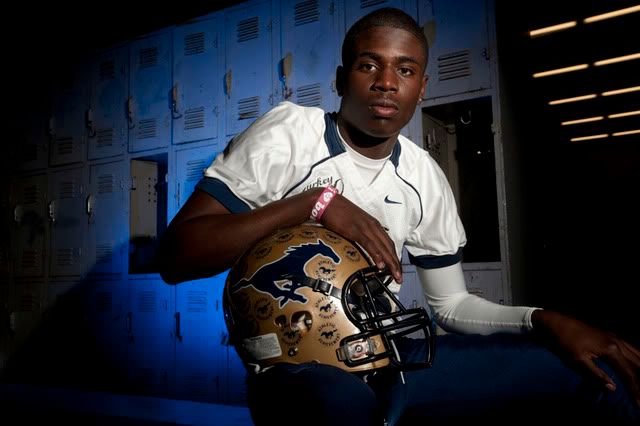

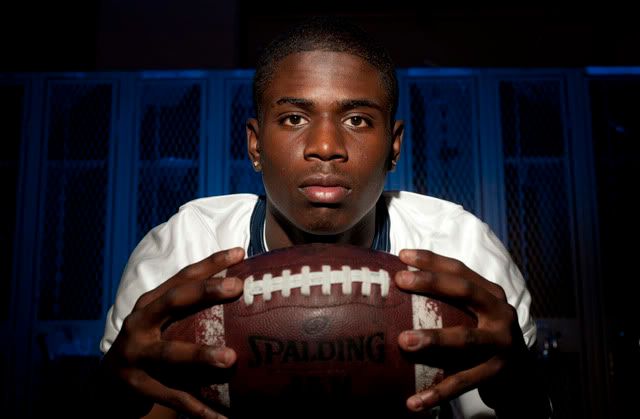

The 6-foot-4 star wide receiver for the Mustangs football team will play in front of thousands at 7 tonight in the 57th annual Turkey Tussle at the Rose Bowl. Holmes said he’ll think of his father’s words, to make the most of the moment and the opportunities that lay before him.

Holmes will withstand the cold November air and soak in the roaring crowd before making his way out of the dark tunnel. It’s more than a moment, it’s a way of life.

Holmes’ upbringing in northwest Pasadena was a struggle, with pressure and influence from gangs at nearly every turn. If not for his uncle, Holmes said, he’s not sure what would’ve happened to him.

“You see on TV the stories about examples of people who made it,” Holmes said, “but to have someone here, physically in front of you, who is family that you can look up to, means the world to me and makes me feel absolutely blessed.”

Darick graduated from Muir in 1989 before stops at Mt. San Antonio College and Pasadena City College led him to Portland State. He was drafted in the seventh round (244th overall) by the Buffalo Bills in the 1995 NFL Draft, and went on to play for the Green Bay Packers and Indianapolis Colts before his season was cut short because of ankle injuries.

Darick draws from his own experience – successful or otherwise – when mentoring Holmes. Darick, while a sophomore at Pasadena, spent 10 months in a juvenile camp. He said his affiliation with the wrong group brought him trouble. Realizing his potential, Darick made a stronger effort to remain focused.

He’s more than just the uncle who played in the NFL. He’s a father figure.

“He’s done so much for me,” Holmes said. “He has his own family to take care of, but yet helps me anytime I need him. He’s always been there to support me.”

Holmes talks to his father about four times a month. They mostly talk about sports and rarely ever, if at all, talk about how and why he landed in jail.

CLICK ON THREAD TO CONTINUE READING THE FEATURE

“He knew that his father was away incarcerated,” said Darick, now a running backs and special teams coach at Muir, “but we didn’t tell him why.”

Two years ago, Holmes said a friend called to tell him he’d seen a clip of an episode from the History Channel’s “Gangland.”

“He said, `Oh, they just mentioned your dad’s name, Karl Holmes, and the guy looks a little like you,’ ” Holmes said.

Not long after that, Holmes was home one night flipping through channels when he stumbled across that very same episode.

“I caught it from the very beginning to the end,” Holmes recalled. “That’s when I really found out.”

What Holmes found out was that his father, 19 at the time, was among the group involved in the killing of Edgar Evans, 13, Reginald Crawford and Stephen Coats, both 14. The teenagers, with no connection to the ongoing warfare between Crips and Bloods, were walking home from a party carrying candy bags. Three other boys were wounded in the ambush attack that was a case of mistaken identity.

Holmes’ father currently is filing an appeal and receiving help from the Innocence Project, Darick said. Regardless of the outcome, Holmes wonders what would have been if his father was physically around to play catch with him, teach him how to drive or even something as simple as learning how to shave.

Holmes recalls his first visit to San Quentin.

“I was a baby when I went,” he said. “I remember they told me they don’t feed them well, so I went to the vending machines and bought a bunch of stuff like Hot Pockets and stuff. Man, he destroyed them when he saw them.”

His first visit was more about getting to know his dad. The second two-hour visit focused on sports. Holmes lets his father know he’s ambitious, telling him specific goals he’s set out for his future.

Next semester, Holmes will take a sociology and speech class at PCC while juggling high school classes, too. He said he wants to raise his 2.8 GPA to at least a 3.2, and has applied to Jackson State, Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo, Arizona State, Arizona and Colorado State.

“Since he was a kid, you knew he was something special,” Darick said. “He talked a lot on the football field, but you knew that if he set his mind on something, he would accomplish it.”

Holmes’ ultimate goal is to reach the NFL, but along the way he’s set out small goals to get there. He runs track, and already he’s receiving interest from said schools. Holmes would like to earn a football scholarship and later walk on to the track team. Regardless, he’s set his mind on majoring in history, and the reason’s simple.

“My teachers made it fun and they made it interesting for me,” Holmes said, quickly mentioning Muir history teachers Manuel Rustin and Mike Harrison, who also doubles as Darick’s godfather and is “like a grandfather” to Holmes.

When it’s all said and done, Holmes said, he wants to return and teach at Muir, where it all started for him – but not just teach.

“I want to be an athletic director, coach the Pasadena Ponies and coach the Mustangs,” he said. “I want to come back and give back to my community, and show kids in the future that they can make it, no matter how they grew up.”

The questions, however, will be inevitable when future friends and mentors ask about his upbringing and his parents.

“I’ll tell them I lived with my mom and that my uncle was like a father figure to me,” he said. “I won’t get into detail with them about my dad, because they don’t really have to know. At the same time, it’s also something I don’t hide, because I feel I have nothing to hide.”

Holmes said he sometimes catches himself thinking about his own kids and how he’ll raise them. Holmes said the simple idea that he’ll be around to watch them grow up is special to him.

“My dad doesn’t think I’m taller than him,” said Holmes with a wide smile. “But he’ll see when I see him and we stand back-to-back.”

Holmes’ grandmother, Erma Martin, often reminds him that he’s blessed, regardless of what anyone else might say.

“She always tells me,” Holmes said, ” `Boy, when you make it, you’re gonna have a story to tell.’

“If it all goes according to plan, I’ll make her and my whole family proud.”

miguel.melendez@sgvn.com