Several thousand fans pour down the Rose Bowl, swarming players for autographs and pictures on a cool April night. The UCLA football team has just wrapped up its annual spring game. Not thrilling football, but football nonetheless. The school announces a crowd of exactly 20,000.

Perhaps no one is happier to see them than Dietrich Riley. For the past 18 months, the former star recruit had been recovering from a frightening neck injury, one that erased what would have been his junior season.

He was ready for his comeback.

Riley hugs a teenage girl, then poses for a picture with two others. A spiky-haired boy comes up to him and requests an autograph on his replica jersey. The father asks Riley to write all the way across, and he obliges. All the way? Why not? He scrawls his name, filling the blank above the “1” — his number.

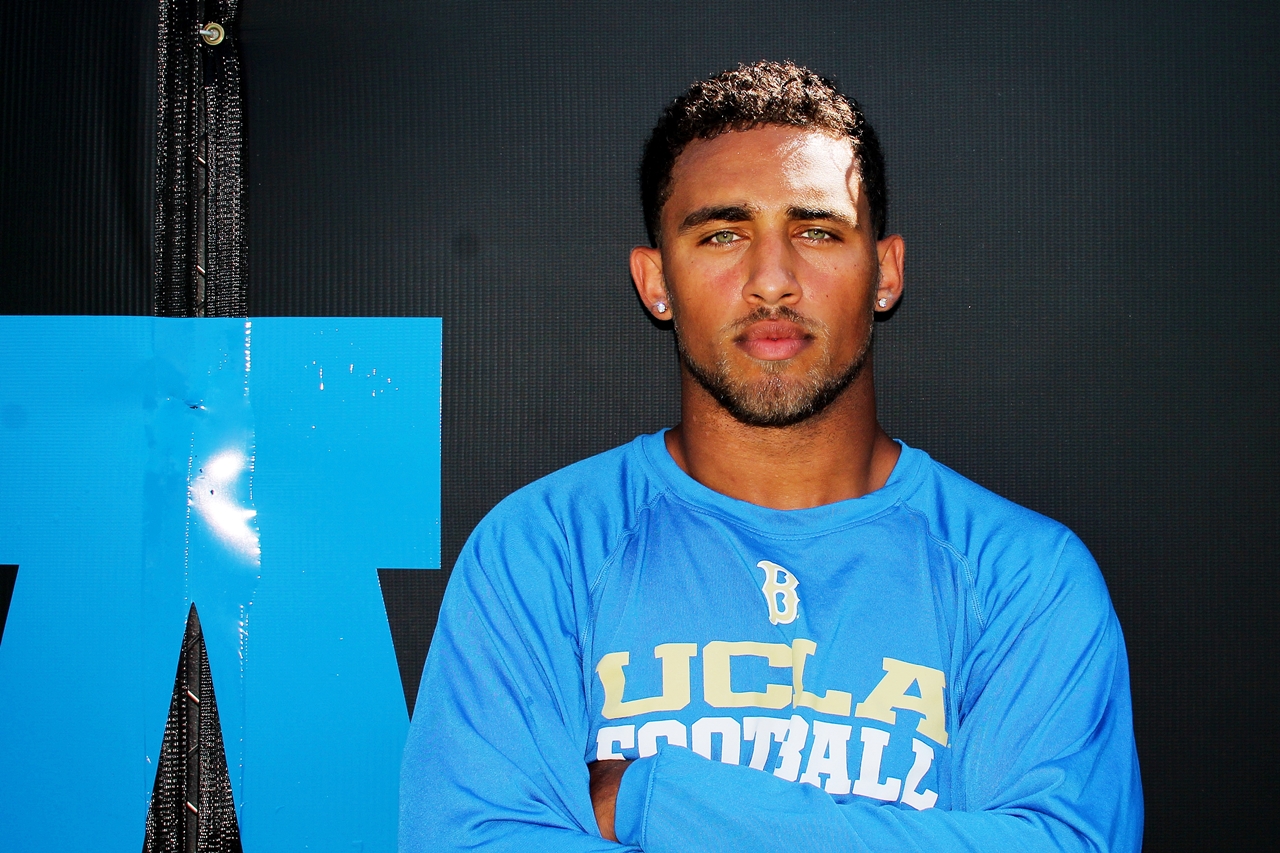

The 6-foot, 200-pound safety smiles as he soaks in the attention, his green eyes glistening. Riley believes he will return, his neck even stronger than it was before the injury. He practiced in spring with a red jersey on, but separated his shoulder when his arm got caught in a one-on-one drill. Only a minor setback, he says.

He does not know that his football career will officially end in three months.

***

Almost every anecdote from Dietrich Riley’s playing days involves hitting. He was always aggressive, so much so that his mother worried that other parents would complain.

Freshman Bruins safety Tyler Foreman, who idolized Riley when both played Pop Warner at Pasadena’s Victory Park, recalls the hit on Oregon State’s Jacquizz Rodgers in 2010 — one that popped off the tailback’s helmet. “It was one of the biggest hits I’ve seen in college football,” Foreman says.

It began on the front yard. When he was still in elementary school, Riley and his cousin would line up and go “heads up” at each other.

“That’s when I knew, like man, this is what I’m made for,” he says. “This is me. Throw my body around. Diving and making tackles. Cracking and making hits. … That’s when I knew I was built for contact.”

His mother, Marika McWhorter, never knew much about the sport. She wanted him to play baseball. Her father, Sam, had been a promising infielder decades ago, eventually signing with the Cleveland Indians organization. In 1963, he set the record for stolen bases at Pasadena City College. A yearbook picture captures him swiping home plate.

Even his godmother, Melinda Helms — who shared his love for the gridiron — preferred that he play basketball.

Riley never doubted his future. He never had the patience to stand at first base. He loved basketball, but it didn’t call to him with equal fervor. He belonged in pads and a helmet, his first — a San Francisco 49ers costume set — bought for $50 when he was three years old. The first time he put it on, he posed in a three-point stance.

He always played with the older kids, but an eighth-grade growth spurt helped turn him into a legitimate prospect. During his sophomore year at St. Francis High, USC gave him his first offer. Nearly 20 more followed. He was named to all-star teams by every local newspaper. Rivals.com rated him the No. 9 safety in the nation.

Letters were postmarked all over the country, from Norman to South Bend, from Ann Arbor to Tuscaloosa. His family set up a matrix to help him decide, quantifying such factors as: winning tradition, weather, campus quality, coaching staff, distance from home. Out of 10, UCLA scored 9.26 overall — easily the highest of any school.

His decision still stretched on, his mind wavering until the morning of his announcement on ESPNU. Swayed by Rick Neuheisel’s promise of a rising program, Riley signed his national letter of intent on Feb. 3, 2010.

He made an immediate impression, playing in 11 games as a freshman and stamping his presence by popping off Rodgers’ helmet. The next year, he made four stops in his first career start, earning four more. But when coaches sent him back down to second-string, he lost focus.

In the week leading up to the Bruins’ Oct. 29 home game against Cal, Riley admits he had a selfish attitude. He didn’t study the game plan enough, didn’t buy into what the coaches were preaching. If he had, he says now, he may still be playing football. He remembers the play well.

With a 24-14 lead in the fourth quarter, the Bears started a drive on their own 20. Four plays in, Cal had a first down on UCLA’s 28-yard line. Tailback Isi Sofele ran toward the sideline. After gaining six yards, he and Riley collided.

“The guy bounced to the outside and — I wish I had it back — I lunged into the tackle,” Riley says. “I didn’t run my feet through. I didn’t trust my speed. I didn’t run to him. I broke down early and I lunged. I kind of ducked my head and I hit his hip.”

Riley didn’t get up. For what felt like half an hour, the Rose Bowl was almost silent, his teammates and the audience both waiting for any positive sign. He was carted out to the hospital, but the initial prognosis was positive. Neuheisel told media that it was likely just a stinger.

Three days later, doctors gave him graver news: a herniated disc between his C3 and C4 vertebrae. Spinal stenosis had left him vulnerable to injury, and the examination revealed that only six to eight millimeters separated the two bones — well below the average 10 to 12. He needed surgery to prevent further damage.

After consulting with multiple professionals — including Dr. Robert Watkins, who operated on Peyton Manning — Riley underwent surgery the following April. A piece of metal and bone from his hip were fused to his spine. He left the hospital in less than 48 hours.

His loved ones were conflicted. Riley’s mother wouldn’t force him out of football, but she also didn’t want to see him put his body at risk. Even now, when she sees another injured player, she feels the same fear well up. She never liked the sound of football pads hitting.

Helms was hesitant too, but she wanted Riley to make the right decision on his own. “It’s the belly of the beast,” she says. “That’s what that game is.”

Confusion trailed the following months. Riley says that Dr. Jeffrey Wang, the surgeon who operated on him at UCLA Medical Center, cleared him for activity in September 2012. In October, he began traveling as part of the scout team. He participated in the most recent spring camp, albeit without contact. The school wanted to make sure he was safe. After consulting with Watkins and other doctors, UCLA’s medical staff told Riley in July that he had to retire.

He says he has yet to cry.

In a grainy home video dated June 17, 2003, Riley walks along the backstop at a baseball diamond in Arcadia, getting ready to shake hands after a Little League game. “THE FIELD OF DREAMS” is painted on the outfield fence behind him. He turns toward the stands and blows a kiss.

Another childhood relic, this one undated. On an orange, basketball-shaped piece of construction paper, Riley wrote: “When I play the sport basketball, I always have the spirit inside me. When I’m playing, I hear the crowd screaming Dietrich! Dietrich! Dietrich!”

Now 21, he sits on bleachers at Spaulding Field and stares out at his team’s practice facility. The on-campus stadium Neuheisel sold to him never materialized. Neither did the Nike deal. But the coaching change that followed the six-win 2011 season has transformed the program in other ways. After a nine-win debut, Jim Mora has positioned the Bruins as a budding conference power. For the first time in a decade, Rose Bowl berths and national championships aren’t complete pipe dreams.

Riley has missed all of it, and the frustration in his voice is palpable.

“I didn’t want to be that guy from Pasadena who had all that talent, comes to UCLA, and he folds. Disappears,” he says. “What scared me the most when I first medically retired — I just happened to think about that — no one’s gonna know me anymore. That was my biggest fear.”

The retirement devastated him, but being away from practices only made him feel worse. He couldn’t bear to hear defensive backs Anthony Jefferson and Brandon Sermons, his longtime roommates, talk about everything he couldn’t do. Once secondary coach Demetrice Martin suggested he become an undergraduate assistant, Riley jumped at the chance.

“There was no way I was going to be able to sit around at home and just become a regular college student,” he says.

When UCLA closed fall camp in San Bernardino, players signed autographs for the hundreds who had driven into 100-degree heat. For the first time, Riley was out of uniform, anonymous. Only a handful of fans approached him.

***

He says God watched over him that night at the Rose Bowl. As he lay near UCLA’s 20-yard line, feeling slowly trickled back down his arms, his legs. Once strapped to a stretcher, he pointed up at the sky, signaling to 50,000 fans. At around 1 a.m., he was released from Pasadena’s Huntington Hospital, a burning right shoulder his only lingering symptom.

“Why am I able to walk? How am I able to escape that episode?” Riley says. “I was surfing the web last night. A kid from Kentucky, a 16-year-old died from a spinal injury. C3, same one as me. And he died. Why me? How was I able to escape that?”

This is the expected narrative: The consummate jock discovers renewed appreciation for his health. He realizes there is more to life than football, finds other avenues, succeeds. The injury becomes a blessing in disguise, a lesson for others to expand their horizons beyond the sport.

Dietrich Riley wants to get there. Aside from his injury, his biggest regret is not talking to more people on campus, not breaking out of his football clique. If coaching doesn’t work out, he has other options.

On track to graduate from UCLA with a history degree, he also enrolled in a theater class. Riley had dabbled on stage at St. Francis High, playing Othello in a school production. His instructor was actor Michael Tucci, who played Sonny in the movie “Grease”. Tucci often told Riley he could be more than a football player — a rare message for a teenager with college recruiters flooding his high school campus.

A few weeks ago, Riley sent headshots to modeling and acting agencies. He auditioned for pilots, including one for an HBO series. Sports networks have talked to him about job opportunities.

But he still feels cheated, his dreams cut short after 19 games and 57 tackles. Every day, he laces up the same cleats he wore when he injured his neck: white adiZeros with black stripes, size 11.5, tape residue still showing. During practices, he prefers to stand behind the end zone rather than on the sideline. He smiles often, because being peripheral to the game is better than being nowhere near it.

“If I were to not be able to walk again,” he says, “if I were to not be able to breathe again — I would rather have it happen on the football field. This is my comfort zone. This is what I love. Smell the grass, the cleats. Everything. I appreciate this game that much.

“If I had any opportunity to lace them up again, I wouldn’t hesitate. People saying, ‘You still have that spine injury’ — I don’t care. This is all I know.”

Photos by Los Angeles News Group staffers Jack Wang, Sarah Reingewertz and John Valenzuela, and from Dietrich Riley’s Instagram.

A version of this story appears in the Sept. 5 edition of the Los Angeles Daily News and other LANG newspapers.